Riccardo Tedeschi and Alessandro Brun of Masque Milano with Perfumer Luca Maffei (middle)

Over the past year, I couldn't help but notice many passages mentioning that there was something akin to an Italian revolution taking place in artistic perfumery..

“I will think of 2016 as the Renaissance of Italian Perfumery, making its mark on a global scale”. –Michelyn Camen, Editor In Chief

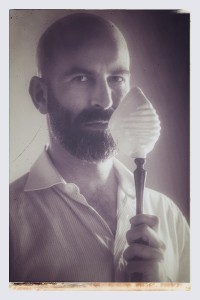

Meo Fusciuni Giuseppe Imprezzabile (photo courtesy of Meo Fusciuni)

“Cristiano Canali is one of a new school of young Italian perfumers along with Meo Fusciuni, Antonio Gardoni and Luca Maffei who are reshaping the dynamics and textures of European niche perfumery.”(December 2015) – The Silver Fox,

The Financial Times recently wrote in an article "Italian Perfumes That Are Wearable Art", that "one not need be a marketing specialist to notice that Italians wear scents differently from the French or Germans." Many perfume enthusiasts and experts recognize that we are experiencing the beginning of a generational shift and believe that Italian brands are playing a growing role, especially in the "niche" segment of perfumery. I would like to shed some light on the determinants of the Italian 'Rinascimento" which consitute the the true origin of what is taking place today.

BACK IN TIME: To better understand this current revolution, we must be aware of what happened in the past. To really understand “renaissance” we need first to know the origins of what we are discussing.

Lorenzo by Girolamo Macchietti (16th century)

Nurturing innovation in Florence: In a recent paper published on the Harvard Business Review, the author Eric Weiner explains how “Renaissance Florence was a better model for innovation than Silicon Valley is”, praising the developments of crafts and arts in the Florentine “Bottega” under the patronage of the Medicis, and indicating some beneficial practices which were largely responsible for the outstanding achievements:

- mastering the art of “talent spotting” and employing wealth to patronize young talents;

- mentoring apprentices for long years, so that they could learn the tricks of the trade;

- “betting” on younger generations with potential rather than experienced masters;

- rather than attempting at restoring the glorious past, leveraging catastrophes to create something entirely new;

- appreciating the value of healthy competition, recognizing that – especially in crafts and arts – both “winners” and “losers” benefit from it;

- looking to different cultures and the past for inspiration, and recognising that innovation involves a synthesis of ideas – some new, some borrowed – and there’s nothing wrong with that.

La Pietà by Michelangelo Basilica of San Pietro

The paper provides plenty of anecdotal evidences to support said practices. Such as the day in which, while strolling through Florence, Lorenzo “il Magnifico” couldn't help noticing a lad sculpting a faun (the half-man-half-goat mythological creature) and at once recognized the young fellow’s hidden talent; the boy, hosted at the Medicis residence, worked and learned alongside Lorenzo’s children. That lad happened to be Michelangelo Buonarroti. And had Lorenzo skipped his daily stroll that day, there would be no “La Pietà” to behold in Vatican City today.

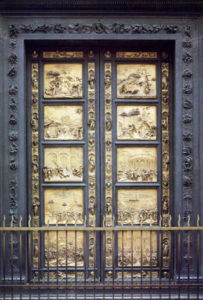

The Gates of Paradise – Lorenzo Ghiberti

Another impressive anecdote regards the determination (and foresight) with which Andrea del Verrocchio kept in his workshop a young artist from an “illegitimate” family, as an apprentice for ten years; notwithstanding his brilliant and genius, the boy had to start from the humblest tasks such as sweeping the floors and cleaning chicken cages. The apprentice’s name was Leonardo.

And also when deciding who was to paint the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling, Pope Julius II appointed the still relatively young Michelangelo, preferring talent and potential over experience. And that definitely turn out to be the right choice. The author also briefly mentions the beauty contest for the North Gate of the Florence Baptistery, won by the “outsider” Ghiberti (“the Gates of Paradise” would then become his undisputed masterpiece) and creating a big disappointment to Brunelleschi which, without letting the failure discourage him, travelled to Rome to study ancient structures and “brought those lessons home to build the city’s iconic landmark, the Duomo”.

Clemente VII marries Catarina and Henri II, Uffizi Storeroom

Caterina de’ Medici and the court of Henry II: On April 13th, 1519, the granddaughter of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Caterina, was born. Her mother and father died soon after her birth, so the orphan was raised by nans, which gave her an extremely curated education, based on the multifaceted essence of Italian Renaissance. Caterina was barely 14 when her wedding with Henry II was decided (as per the arranged weddings custom, bride and groom-to-be had never met before). Allegedly, 60 ships with the Medici and Pope entourage departed for Marseilles with Caterina to celebrate the nuptials. Caterina, along with her dowry, brought to France a large staff, including her trusted tailors, jewellers, cooks, sommeliers.

Rene Le Florentin nee Renato Bianco

One noteworthy loyal servant was Renato Bianco. His profession was concocting fragrances for his mistress: he was the Queen’s perfumer. Having opened a boutique in Pont Saint Michel, Renato soon acquired popularity among the Parisienne elite patronizing his business, and earned the epithet René le Florentin, If I were to pick one pivotal year in the history of modern perfumery, I would definitely pick 1533, the year of Caterina’s wedding and of the entrance of René le Florentin to France.

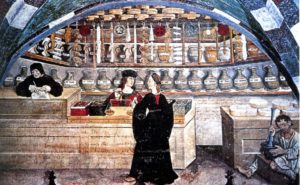

Medieval Apothecary Shop,15th Century Italy

Before 1533, Venice and Florence were the perfume capitals of Europe. Monks and friars of different congregations, as well as "muschiari", distilled fragrant materials and concocted ever-new recipes in small laboratories. Thanks to the contribution of Caterina and René le Florentin, the passion of the French court for the fragrant and ephemeral pleasure grew rapidly with time, to the point that the reign of Roi Soleil is referred to as “the perfumed court”. Under the kingdom of Louis XIV, the monopoly of perfume distribution was granted to glove-makers – hence named gloves and perfume-makers (and later on, with the market of leather gloves declining, simply perfume makers). Flowers cultivation in the South of France became a major business.

Catherine di Medici 1560 by François Clouet and perfume "poison gloves"

Renaissance – a craft not an art – 14th to 17th Century: Throughout the Rinascimento (14th to 17th Century), many people dedicated their lives to perfume-making – friars, muschiari, glove-makers. Yet all of them were distilling essences, mixing essential oils, and employing them in different end products – not just perfumes, but also powders, pomanders, scented gloves etc. -, in small-scale labs and adopting artisanal techniques. Before perfumery started affirming itself as a specific industry, inherent craftsmanship was nurtured by the dedication of artisans. Perfumery was a craft, an artisanal endeavour. Not an artistic one.

Vintage Houbigant Bottles Fougere Royale L'ideal Quelques Fleurs from the Collection of Kevin Verspoor for CaFleureBon

The birth of the perfumery industry – 18th and 19th Century: By the 18th Century, the growing market and the refined materials processing and transformation techniques created the opportunity for perfumes manufacturing to develop on a much larger scale. The first large perfume houses – still operating today – were established: Houbigant in 1775, Lubin in 1798, Guerlain in 1828, just to mention a few, along with glass manufacturers such as Baccarat and Lalique (established in 1764 and 1885, respectively). The perfumery industry was born. Perfumes would be produced through industrial processes and the growing volumes would, eventually (not before a lengthy transformation process of more than a century, though), lead to mass-production.

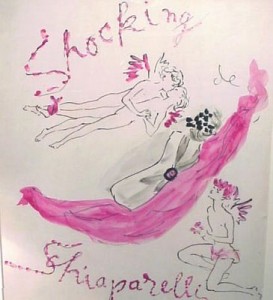

Marcel Vertes Shocking for Shiaparelli

Designer perfumes – (first half of) 20th Century: Throughout History, perfume constituted an essential element of both personal hedonistic pleasure as well as a social marker for people of virtually every social class. For this reason, perfumes are the quintessential luxury good [NB: the debate of “what luxury is” would be too long to address here; those interested in having more details could refer to Brun and Castelli, 2013]. Yet the concept of luxury itself was undergoing a significant change: in the XX Century a completely unseen phenomenon started, which is referred to as “democratization of luxury”. Many fashion designer and luxury houses introduced a fragrance line as an attempt – often successful – to extend the brand's reach to a new, more accessible and alluringly profitable product category. Coco Chanel back in 1910, Lanvin in 1924, Jean Patou in 1925, Elsa Schiaparelli in 1934 and so on.

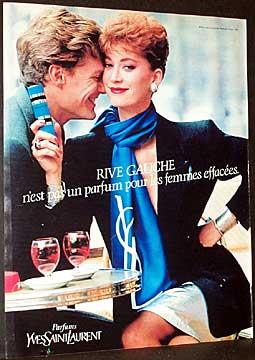

1981 Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche Ad

In the second half of the XX century, the number of designer fragrances available in the market simply skyrocketed. With the advent of designer perfumes, even the working class – who could never afford a designer dress – would have access to the coveted world of luxury. Borrowing the catchphrase from the seminal work of Silverstein and Fiske, we can speak about “Luxury for the Masses”.

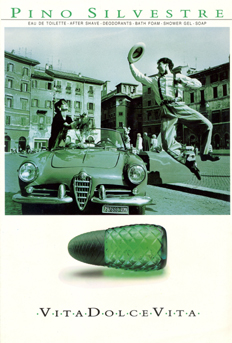

Many sources give Pino Silvestre launching in 1955, that is not correct (1946)

The Italian economic miracle – 1950 – 1963: In the two decades following WWII, Italy was blessed by a period of strong economic growth. Along with a radical transformation of the country’s economy – bringing a rural country into the Gotha of the largest global industrial powers – society and culture were also revolutionised. Along with the Vespa (1946), the Olivetti Typewriter (1950), the Fiat 500 (1956), as well as the first Italian fashion show at Pitti (1951) – often regarded as the birthdate of Italian fashion, Italian scent creations getting internationally acclaim included perfumes such as Acqua di Selva ( first launched in the mid-1930s and relaunched Post War 1949) and Pino Silvestre (1946) which was inspired by the success of Acqua di Selva.

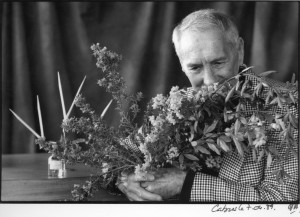

Edmond Roudnitska 1969 (photo kindly from Michel Roudnitska's Archives)

Artistic perfumery: 1968 and the 70’s: Master perfumer Edmond Roudnitska, in 1967, provocatively declared: "it seems lhat today there is no man today capable of launching a Chanel n.5”. The creator of Eau Sauvage meant that creative perfumers and perfume houses should anticipate the times, innovate, rather than follow trends and market tastes.

Annick Goutal photo courtesy of Camillle Goutal

It was probably with that idea in mind that pioneers like Gautrot, Knox-Leet and Coueslant (founders of Dyptique), Jean Laporte (L'Artisan Parfumeur), Annick Goutal created the first niche / artistic perfume houses, succeeding in creating a disruption. It all happened very quickly, with one of the first forewarning of a new era in the history of perfumery probably being the launch of Diptyque's first fragrance, L'Eau, in 1968. In a few years many other followed: L'Artisan Parfumeur was established in 1976 with a strong focus on nature and "a desire to do things a little differently" and two years later launched the revolutionary Mûre et Musc; the Annick Goutal House opened in 1981 and introduced Eau d'Hadrien in the same year; and so on. What was new in Diptyque's L'Eau was not the formula – it was inspired by an old Eau de Toilette recipe; rather, the products of these avant-garde brands were the brainchildren of the founders and embodied their creativity, personality, passions and childhood memories. Please pay attention to these terms – Creativity, Personality, Passion – as they definitely play a major role in artistic perfumery today also. Modern artistic perfumery was born.

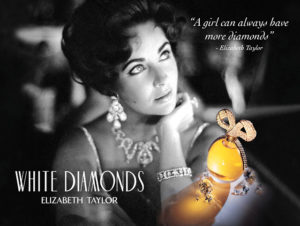

Elizabeth Taylor's White Diamonds, 1991

Celebrity fragrances – 80’s and 90’s: Besides a few cases in the 50's, it wasn't until the last two decades of the past century that celebrities also were enticed into a business where – with a fancy brief and a sound marketing team – almost everybody has a chance to put her name on the next blockbuster fragrance. This was just one of the trends which contributed to the soaring number of new launches, with the 3rd millennium consumers literally overwhelmed by a mind blowing 1,000+ new fragrances every year. Yet less than 5% of the new launches will actually succeed staying in the market for more than two years. As a general trend, experts commented, creativity plummeted and was promptly replaced by a quite advanced use of marketing techniques.

Italian Private Label Production – 80’s and 90’s: While the consumer market of perfumes was split between French brands of haute perfumery and designer & celebrity brands, Italy kept playing an important role below the radar… Several brands in the perfume and cosmetics industry had their production actually carried out in Italy – frequently resorting to outsourcing to local suppliers. When looking in hindsight at the latest developments in the business of perfumery, one should not overlook the contribution of Italian laboratories, private label productions and so on… But this is a completely different story. I promise, one day, to tell you more about this.

And now? Neo-Artistic Perfumery – 2000-2015: Since the turn of the Century, we witnessed to the launch of a fairly large number of "niche" fragrance houses, which are really revitalizing the very artistic impulse that inspired, almost four decades ago, the creation of the first wave of artistic perfumery houses. In a 30B$ fragrance market, there is a small yet significant fraction of connoisseur consumers trying to escape from mainstream brands and relentlessly hunting for the next hidden unknown brands. Artistic perfumery avoids advertising, hence remaining a well-kept secret only discovered through word of mouth and the commendable endeavour of a small group of extremely selective perfumery boutiques (and, lately, some exclusive department stores). With the turn of the century, a number of trends contributed to the spread of artistic perfumery: fairs dedicated to artistic perfumery (Fragranze since 2003, Esxence since 2009), aficionado communities (both real – Sniffapalooza since 2002 – and virtual), prizes and awards (the Art and Olfaction awards since 2014, the "Indie Category of the Fragrance Foundation Awards), cultural events, blogs (Editor' s note: Must mention Contributor Ermano Picco of La Gardenia nell Occhiello), and perfumery 101 training courses.

“New” artistic fragrance houses are clearly showing a desire to move away from mainstream, and to include lofty cultural elements into their fragrant endeavour.

Kilian Playing With the Devil 2013

Customers can choose – branded perfumery vs artistic perfumery: The recent acquisitions of (amongst the other) Frederic Malle and By Kilian are a further proof that, nowadays, branded perfumery is totally in the hands of the major Luxury Groups. Not uncommon, as well, the acquisition of historical Maisons with the aim of reviving them. Artistic perfumery brands shall not defer to the dominance of branded perfumery – rather, they are to keep going along a path of creativity and passion, being true to the original spirit and DNA.

Art Deco Perfume Ad Milano

CRACKING THE CODE OF ITALIAN ARTISTIC PERFUMERY!: So we finally ended our historical retrospective, and arrived at 2017. Why are so many perfume writers and critics speaking about an Italian revolution in artistic perfumery? Is there such a think as a generational shift? Being an “insider” in the Italian Artistic Perfumery community, but at the same time having the Scientific Researcher’s perspective, I’d like to share with CaFleureBon readers the key findings of an analysis, which I have compiling over the past few years:

Antonio Gardoni of Bogue

- Italy is proud of its outstanding tradition of perfume-making. Many features, which are now perceived as “Artistic Perfumery”, have always been part of our tradition. So the “Italian revolution” is first of all an “Italian reaffirmation”.

Dr. Cristiano Canali a Rising Star of Italian Perfumery

- The habit of betting on “the next generation of perfumers” rather than resorting to one of the star-noses of artistic perfumery has many more cons than pros (think about it: it is riskier, it will probably take longer, the kind of advertising you can get by appointing a rather unknown perfumer is nothing compared with what a big name could do). Yet somebody did it. Exactly like the “talent-scouting and patronizing” and “betting on the younger” attitudes which made Italy great during the Renaissance.

Sauf Perfumes: Fillipo Sorcinelli's flacons inspired by the stops of the great organs

- How are Italian noses and brands “reshaping the dynamics and textures of European niche perfumery”? By taking inspiration from the past, picking elements – not only from different cultures, even from different forms of art – “deconstructing” them and then “[reconstructing] in a new shape”.

Rubini Profumi Fundamental

- Italians are not creating their visual identity adopting academic marketing or branding tools. It is so obvious, so patent that many brands have a very coherent (visual) identity being the natural of the founder’s (or creative director’s) personality. Using the sense of aesthetic and the artistic education (most of us were born and bred in an open-air museum) “wrapping the result in the most beautiful packaging money can buy”.

- How are Italian brands working together? Working side-by-side in a friendly, healthy competition. Supporting each other whenever possible, recognizing that “both winners and losers will benefit”!

- “Innovating through design” is another paper appeared on the Harvard Business Review in which the author, Roberto Verganti, explains how the Italian heritage is one of the key reason behind the success of Italian design, discussing cases such as Alessi, Flos, Artemide, Kartell and others. In all these Italian design companies, the push to innovate products does not come from an urgency to please customers’ needs (the so-called “Market Pull”). On the contrary, these companies are belonging to an eco-system of very innovative companies, organizations, and individuals (the author mentions Lombardy’s “community of architects, suppliers, photographers, critics, curators, publishers, and craftsmen […] as well as the expected artists and designers”.) The equivalent, in perfumery, of a Market-Pull strategy would be launching a fragrance belonging to a certain olfactive family, since that very olfactive family is the best-selling one in our target market. In our eco-system, several fragrances are created after having had a friendly exchange of opinion with a competitor, finding out a certain raw material by serendipity, through a collaboration, and in many other (unprecedented, and even unthought of) ways.

Alessandro Brun

Being Italian reminds me every day how we are – at the same time – a nation of artists – with an innate sense of beauty and elegance -, generous patrons and mentors, insatiably curious explorer. This is what I see reflected in the most promising artistic Italian brands.

–Alessandro Brun, Guest Contributor and Co-founder and Creative Director of Masque Milano

Author's Note: Thanks to Ermano Picco for his kind assistance in tracking down launch dates of these historical fragrances.

Art Direction: Michelyn Camen, Editor-in-Chief with the note that I could not include every innovative Italian Artistic Perfumes photos, forgive me; you know who you are and you are integral to this article. To the many many global bloggers who have advocated this Renaissance we celebrate you all.

READINGS and BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alessandro Brun and Cecilia Castelli, “The nature of luxury: a consumer perspective”, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, Volume 41 Issues 11/12, 2013

Michael J. Silverstein and Neil Fiske, “Luxury for the Masses”, Harvard Business Review, April 2003

Roberto Verganti, “Innovating Through Design”, Harvard Business Review, December 2006

Eric Weiner, “Renaissance Florence Was a Better Model for Innovation than Silicon Valley Is”. Harvard Business Review, January 2016