Close-up of George Segal’s “Gay Liberation” ©2020 Charenton Macerations

Seven years ago, I wrote a series of articles for ÇaFleureBon titled, A Queer History of Fashion (and the Untapped Queer Potential of Fragrance). In that series, I looked at how queer peoples and subcultures exerted their influence on fashion history, covering everything from LBGTQ+ designers and fashion icons, to the cultivation of various queer-coded styles of dress. Fragrance was discussed in tandem, comparing how these same cultural shifts in fashion did (or did not) shape olfactive history. Apart from a few noted exceptions, fragrance, I concluded, had yet to realize its queer potential. When fashion went bold, fragrance stayed conservative; when fashion was nuanced, fragrance was closeted.

In the Fashion Institute of Technology’s, A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, queer identity took centerstage; identity (here a predominantly Eurocentric, cisgendered gay white male identity) informed the now-reading of the queer fashion objects on display. How certain fashion movements challenged normative conventions of dress was presented as a consequence of a particular subset of queer influencers’ actions. “In their hands, fashion was a tool to expose, question and challenge the boundaries of society’s norms, particularly norms of sex and gender.” Noticeably absent from that presentation were the equally important contributions from Queer and Trans Black Indigenous People of Color (i.e. Josephine Baker, blaxploitation, ballroom culture…). This narrow understanding of queerness echoes the ongoing criticisms directed at the world of mainstream fashion.

As for fragrance, the postwar period demonstrated how heteronormativity was reinforced olfactively. Through the crafting of “for him” and “for her” categories, odor, once a genderless extension of the natural world, was transformed into yet another mode of gendered constraint. Idealized versions of men and women were now something to be packaged and bottled. Because of this intentional gender segregation, people still struggle to describe scent outside the confines of these binary “masculine” and “feminine” fragrance types. Ingredients and fragrance families have been colonized. To queer fragrance is to strip away these preconceptions, replacing them with a question: What purpose do they serve?

Much has changed for fashion and fragrance in the last decade. From marriage equality to Pride inspired collections, gender transgression to genderfluidity, fashion has undeniably been having a queer moment. While these increased efforts towards inclusivity have certainly opened doors for some, others in the LGBTQ+ community have remained noticeably absent (QTBIPOC, trans men, and masculine non-binary people are particularly underrepresented). That being said, presentations from the likes of dapperQ’s Anita Dolce Vita and Opening Ceremony’s Humberto Leon and Carol Lim have helped raise not just the amount of queer visibility, but also championed the equally important causes of diversity and ownership. Fragrance, too, led by an ever-growing group of indie disruptors and a surge in genderless/gender-defiant offerings has finally begun recognizing the importance of its LBGTG+ audiences. However, the range of queer scent narratives available has continued to be limited.

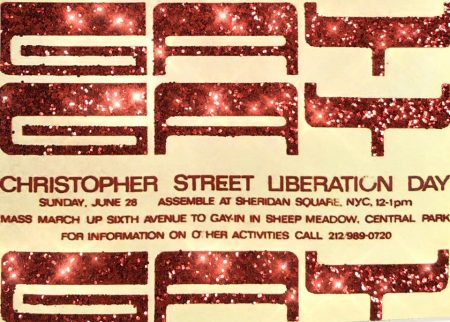

Original 1970 Pride March Poster, NYPL

June 28th marks the 50th Anniversary of the first Pride March in New York City (née Christopher Street Liberation Day). That first Pride March was a rallying cry for liberation: a rebellion against corruption and brutality. Thousands came out that day in solidarity. A movement was born.For queer fashion and fragrance, that rebellion rages on.

The 2010s: Queer Mainstreaming of Fashion

(left) Ashleigh Good and Kati Nescher for Chanel Spring-Summer 2012, vogue.com (right) Sharon Needles for Betsey Johnson Spring-Summer 2015, cosmopolitan.com

The 2010s was a decade where queer culture found itself shuffled from the margins into the mainstream spotlight of fashion. A noticeable cultural shift first became evident during the fight for marriage equality. In Chanel’s Spring-Summer 2013 show, matching brides Ashleigh Good and Kati Nescher closed the show, walking down the runway hand-in-hand (designer Karl Lagerfeld’s declaration of support for marriage equality executed sartorially). Later on, Betsey Johnson, for her Spring-Summer 2015 “Pre-Nup” Collection, assembled a runway cast that included same-sex couples, trans models, and drag queens; here marriage equality may have been the theme, but the marriage of punk and bridal stole the show. On June 26, 2015, with the US Supreme Court’s landmark 5-4 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, marriage equality became the official law of the land. These newly won legislative freedoms would be accompanied by an exponential increase in queer visibility within the fashion world.

(left) Anja Gockel Spring Summer 2017, designscene.net (right) Cara Delevingne for Burberry Spring-Summer 2018, huffpost.com

Like marriage equality, LGBTQ+ Pride has been an important source of inspiration for mainstream fashion. It is also arguably the most commercialized. The pride flag, shamelessly incorporated into millions of pink-washed products every June, has nonetheless eked out a few noteworthy runway appearances. Anja Gockel’s Spring-Summer 2017 Collection, for example, featured a pride flag inspired full-length halter dress worn by a male model. Christopher Bailey, too, in his final Spring-Summer 2018 soirée at Burberry, mixed the brand’s signature tartan with Pride references. “My final collection here at Burberry is dedicated to and in support of some of the best and brightest organizations supporting LGBTQ+ youth around the world.”

The 2010s: Queer Mainstreaming of Fragrance

(left) Boy Chanel fragrance, Les Exclusifs de Chanel (2016), chanel.com (right) Boy de Chanel make-up ad (2018), chanel.com

For fragrance, the queer-mainstream (r)evolution can be traced to the rebirth of the unisex category. During the 2000s, brands like Tom Ford, Armani, and Dior, marketed their niche exclusive lines without any gender specifications on their packaging, trading masculine and feminine for rare and expensive. If only these launches applied that same level of resistance to binary olfactive descriptors. Though not explicitly labelled “for him” and “for her,” they oftentimes found themselves segregated into these categories at retail where certain offerings still were targeted in an either/or manner. Structurally, too, they offered little in terms of formula innovations. The changes made were mostly superficial, but laid the groundwork for what was next to come. Consider Boy Chanel (2016) as a more contemporary example of this trend. Described as a fragrance that “challenges tradition and transcends gender,” the fragrance’s only real gender transgression was unisex marketing applied to a classic, aromatic fougère. (Side note: Chanel added a Boy de Chanel men’s makeup line in 2018; Chanel Beauty then hired its first openly transgender model, Teddy Quinvilan, in 2019.)

Charenton Macerations Christopher Street (2012), charentonmacerations.com

Drawing inspiration from NYC’s recognition of same-sex marriage, Bond No. 9 launched I Love NY for Marriage Equality in 2012. This self-identified unisex scent featured a spicy “wedding bouquet” mix of florals atop a bed of soft woods. Packaged in a “white wedding” bottle emblazoned with a rainbow flag heart, the presentation was quite literally a traditionally heteronormative symbol stamped in queer iconography; the fragrance was pleasant enough, but felt divorced from its LBGTQ+ subject matter. Conversely, Charenton Macerations’ Christopher Street (2012) took a decidedly different approach in tackling NYC’s history of queer activism. To capture that distinct sense of liberation, queerness was presented in relation to the olfactive environment it rose from. People, places, the music… 400 years of olfactive memories from Greenwich Village were archived and overlapped into a unique chypre-oriental-fougére mix (with a splash of soda). Every ingredient in Christopher Street’s olfactive narrative had its own story to tell: individually and collectively. Crafted by an all queer creative team, Christopher Street launched as the first queer (not unisex) fragrance.

Gucci Mémoire d’une Odeur (2019), gucci.com

Gucci’s Mémoire d’une Odeur (2019) was another instance where queer olfactive narrative was paired with the queering of a fragrance’s structure. “Transcending gender and time, Gucci Mémoire d’Une Odeur blends Roman Chamomile and Indian Coral Jasmine to establish a new olfactive family: Mineral Aromatic” (gucci.com). This “universal” fragrance was crafted by master perfumer, Alberto Morillas, in consultation with Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele. Glen Luchford’s accompanying ad campaign, featuring a mix of cis, trans, and other non-binary peoples (e.g. Harry Styles, Zumi Rosow, Olimpia Dior, and Harris Reed) depicted “a gathering of a free-spirited family, who embrace life by living freely and making memories together” (gucci.com). Here, genderfluidity was the subject of mainstreaming. However, fluidity was presented as predominantly tall, white, thin, and rich, raising concerns about its message of inclusivity and questions about its target audience (Daily Xtra). That being said, Morillas’ new structural olfactive form was quite successful.

Conclusion

Mainstream “queering” involves a recontextualizing of LBGTQ+ aesthetics. However, relying on this tactic always runs the risk of diminishing “queerness” to trendiness – reducing whole identities to mere caricatures. To quote perfumer Chris Rusak, “Products that clearly stretch to appeal as queer-sensible are usually laughable, and in the end, [can] undo a lot of the work the LGBTQ community has done to liberate ourselves.” (Perfumer & Flavorist) Absent guidance from actual queer peoples – people who intimately understand the original source materials – well-intentioned overtures can quickly slide into appropriation and stereotyping. True. Mainstreaming can help increase diversity and representation, encourage gender transgression, and drive innovation. But it can also hinder all of these things. For LBGTQ+ people, the question is always: Is there a genuine interest in our stories, or our are stories simply being co-opted to drive more heteronormative consumption?

In Part 5 and 6 of the series, attention shifts to the counter narrative offered by queer independent fashion and fragrance brands and their quest for increased diversity, inclusivity, and authenticity.

You can follow us on Instagram @cafleurebon @cm_fragrance

–Douglas Bender, Guest Contributor and Founder of Charenton Macerations