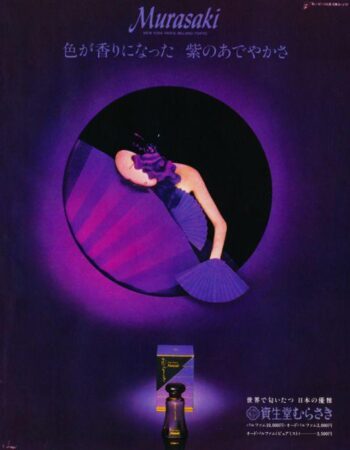

vintage ad Japan wiki Serge Lutens

“Whom the gods would destroy, they first make mad.” ~ from the Latin “Quos Deus vult perdere, prius dementat”.

Surely I think myself mad: it’s always those vintage perfumes about which very little has been written which ensnare me. I want to review them for you – and go doolally in the process. Here we are yet again, in the hands of a superb floral chypre named Murasaki by Shiseido. Is there a wealth of information available? No. Can we identify the nose? No. Has it been reformulated? Yes, a few times – to the point where it is perfectly nice but bears little resemblance to the nuanced original. I was fortunate to come by a bit of well-preserved extrait recently for a reasonable price (that’s rare!), in my quest for some of the less celebrated Shiseido fragrances.

When the company began to collaborate with the U.S. and Italy in 1976 in order to widen its clientele base, perfumes were created which gingerly trod the aromatic tightrope as it strove to appeal to both Eastern and Western sensibilities. Some were wildly successful, while others languished into relative obscurity. Several were reformulated, not infrequently to the point where they eventually became unrecognizable.

The brand Shiseido fascinates me because there isn’t a logical progression regarding perfumers: it’s impossible to say, “Oh, up until year such-and-such, perfumers weren’t disclosed; that didn’t occur until the year.” It isn’t the case. What we can uncover is that when famous noses composed various scents for Shiseido, they were really famous: 1964’s beloved Zen (Josephine Catapano), 1981’s famed Nombre Noir (Jean-Yves Leroy – it was his only big hit – but it’s now firmly ensconced in the annals of perfume history), 1991 Angelic ( Jean-Louis Sieuzac), Féminité du Bois (Christopher Sheldrake and Pierre Bourdon), 1997 Vocalise (Jacques Cavallier-Belletrud), 2000’s Zen version #2, pearl fragrance (Nathalie Lorson), new Zen (2007, Michel Almairac), 2009’s Zen For Men (Francis Kurkdjian and Françoise Caron) amongst them. In fact, I’ve gone through the list, and all the perfumers – save Ms. Catapano – are French, interspersed with talented anonymous creators.

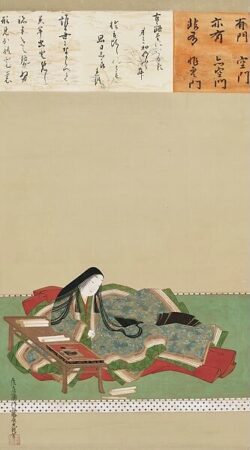

Murasaki Shikibu via The Met, Edo period by Tosa Mitsuoki, 17th C

Shiseido Murasaki is compelling for several reasons: the name itself means the color purple in Japanese – a hue which signifies not only royalty, but nobility, spirituality, and wisdom as well. Those of us who delight in Japanese culture often associate the name with Lady Murasaki (c. 973 – c. 1014-25) – famed novelist, poet, and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial Court during the Heian period (794-1185). Murasaki Shikibu is the author of The Tale Of Genji, which is widely acknowledged as one of the first known written novels – and she was a highly unusual woman for her time: educated in the manner reserved for men, she was tutored in classical Chinese along with the required skills of a young noblewoman – calligraphy, music, and Japanese poetry. She defied many accepted norms of the day.

Murasaki, the fragrance – is yet another hidden marvel of balance and delicacy. While not all Shiseido perfumes may be likened to watercolors, Murasaki can. I am in awe of this unnamed perfumer, who possessed the ability to layer varying olfactory hues so nimbly. If we were to categorize Murasaki, I suppose that it might fall under the classification ‘green fruity floral gently leathery chypre’: what a mouthful.

Louise Bertaux by Serge Lutens via FB page

Crisp bergamot heralds the arrival of bold, resinous galbanum – so very green that it would normally stop you in your tracks – except that in Murasaki, equipoise is everything. Barring the poignant subtlety of ambergris (who embellishes everything she touches), each fragrant component listed below has the potential to seize center stage: indolic tendencies accompany the territory of hyacinth, gardenia, jasmine and lily. Muguet is frequently portrayed in a dominant manner; rose may choose to either round out a scent or grandstand; peach is rarely experienced as anything less than prominent. Next, we consider the base notes, whose lower molecular weight infers greater staying power: musk, sandalwood, vetiver, and oakmoss: any one of these may subjugate less tenacious aromatic elements. And leather? That’s murky to begin with, as it may be a combination of various natural materials and aromachemicals, a fantasy note (think of Habanita’s blend of vanilla and vetiver, which evokes a smoky leathery tone – or the employment of such materials as birch tar, cade, labdanum, saffron, etc.). Yet scented sovereignty never takes place.

Ida’s 15 ml flacon of original 1980 Murasaki parfum

Dalliance. What transpires throughout our journey with Shiseido Murasaki is a poetic dalliance which is neither carefree nor heavy-footed. I refuse to call this fragrance wishy-washy, because I don’t believe that it is: there’s nothing generic or facile about it. It possesses the mystery of modesty, of beauty in proportion – where no single segment clamors for your attention. That is why Murasaki is symphonic in scope, in the tenderest manner; it has no need to soar to a frenzied climax. As harmonious and nature-loving as the affecting Japanese aesthetic in art, its appeal is universal, timeless, and in exquisite taste.

Notes: bergamot, galbanum, gardenia, hyacinth, peach, chrysanthemum, iris, lily, jasmine, lily of the valley, rose, ambergris, musk, sandalwood, oakmoss, vetiver, leather

Shiseido Murasaki parfum was purchased by me and is part of my collection. My nose is my own…

~ Ida Meister, Deputy and Natural Perfumery Editor

Follow us on Instagram at @cafleurebonofficial @idameister

This is our Privacy Policy