Elaine Stritch sings “Ladies Who Lunch” in the original cast of Company, 1970. Photo by Martha Swope©

I’d like to propose a toast

Here’s to the ladies who lunch

Everybody laugh

Lounging in their caftans and planning a brunch

On their own behalf

Off to the gym, then to a fitting

Claiming they’re fat

And looking grim ‘cause they’ve been sitting

Choosing a hat

Does anyone still wear a hat?

… A toast to that invincible bunch

The dinosaurs surviving the crunch

Let’s hear it for the ladies who lunch

Everybody rise, rise

Rise, rise

Rise, rise

Rise, rise

Rise

– “Ladies Who Lunch” from Company by Stephen Sondheim

Dior-Dior’s whole problem was one of timing. Edmond Roudnitska’s lovely last fragrance for Christian Dior was a floral chypre with a strong citrus vein, augmented by jasmine, aldehydes, and quiet woods. And Lord, was she pretty, in the polished, pristine way of Miss Dior but not as virginal. Her lily-of-the-valley note glittered like Diorrissimo’s but was warmer, and she gleamed with the elegance of Diorella but pared down its overripe fruit. Classically constructed, chic as a Chouchou bag, and not one ingredient overdone or out of place, Dior-Dior was perfect for one of Truman Capote’s “swans of Fifth Avenue.” She was a fragrance for the ladies who lunch.

Trouble is, she was Grace Kelly in an era of restless, imperfect heroines like Jane Fonda and Diane Keaton. Soignee Dior-Dior was ponies and country clubs when she made her debut in 1976, created when the fashion zeitgeist was shifting from ladylike images of women to menswear-influenced designs that reflected a growing acknowledgement of the women’s movement and increasing entry of women into the workforce. Sharp green and woody fragrances like Chanel 19 and Anne Klein Blazer were taking over the female daytime perfume market, and opulent, decadent seductresses like Opium would soon make bad girls out of nice girls at night. By the middle of the decade, a burgeoning club scene had taken hold in New York and LA that mixed celebrity with egalitarianism. Not famous? No problem. Spray on some YSL Rive Gauche from its space-age canister, slip on some 6-inch silver platforms, spray your hair purple, strut the line like you’re Bianca Jagger, and watch the red velvet rope drop.

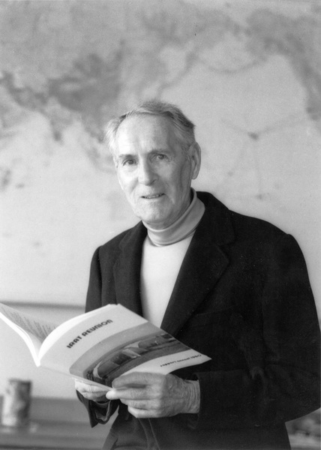

Edmond Roudnitska via Michael Edwards Fragrances of The World©

Against this backdrop, Roudnitska’s swansong for Dior seemed doomed from the start. Fragrance, like fashion and makeup, is a tool for reinventing ourselves, and in the mid-70s, aspirations were changing. Few women now wanted to be a Hitchcock lady when they could be wacky Annie Hall or a gun-toting Charlie’s Angel. Consider some of the famous perfume ads of the time and what they reflected: Charlie’s Shelley Hack, with her confident stride and jaunty pantsuit; Aliage’s Karen Graham decked out in menswear, taking herself on a picnic or hitting the tennis court; Chanel 19’s brash blonde grabbing a man round the neck and pulling him in for a voracious smooch. These gals were direct, confident, take-charge. They wore blazers and trousers and reached for fragrances that reminded them more of dad’s cologne than mom’s perfume.

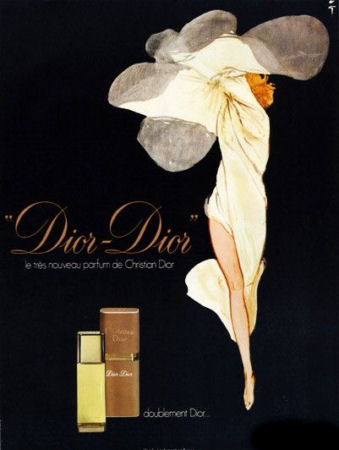

While Dior-Dior is restrained, its animalic heart suggests that Dior, too, was trying to convey a more assertive, sexy woman. Look at the Dior ads from the time, particularly for Diorella, and you see a shift. The famous Rene Gruau depictions of swirly skirts and gloved hands of 1950s and ’60s Dior ads were transitioning to more modern and sexier images of tousle-haired women in unbuttoned white blouses and white slacks, heads thrown back in laughter. And, had Roudnitska run with Dior-Dior’s more dangerous notes, it might have been a hit.

Dior-Dior ad, 1976©

My first encounter with Dior-Dior was as a Roudnitska artifact: a partial bottle I found on eBay. Its top notes were damaged, and my initial impression was that it was the type of high-class, expensive-smelling perfume you wear to the ambassador’s residence when you want to make a good impression without offending anyone. But gradually the fragrance began to reveal its Roudnitska genes: Nothing is overdone, each note balances its partner, the richness of the florals goes so far and then stands perfectly still. But as Dior-Dior developed on my skin, secrets seeped out: that hint of decaying fruit that so marks Diorella, the musky hints of prowl beneath Eau Sauvage’s zesty hedione and citrus. Roudnitska started with the same architecture he used for Diorella, laying lily-of-the-valley, jasmine, and melon on a chypre backbone. While Diorella leans into Mediterranean notes of basil, citrus, and hedione, Dior-Dior embraces the verdant narcissus and green-tinged lily-of-the-valley. This stemmy greenness – quite different form the acerbic, galbanum-centric perfumes that were in vogue in the 70s – gives Dior-Dior’s first half a bright freshness.

But there were more secrets. As Dior-Dior wears, something darker comes out, a tension between the well-bred florals and the warm sexuality animalic jasmine and overripe fruit. A mournful waft of lilac – the flower that always smells of quiet heartbreak to me – drifts by in the heart. Suddenly it struck me that Dior-Dior was the well-to-do, married, trapped sister of her predecessors.

And then I heard Elaine Stritch as the bored, self-mocking Joanne in Company:

Here’s to the girls who stay smart

Aren’t they a gas?

Rushing to their classes in optical art

Wishing it would pass

Another long exhausting day

Another thousand dollars

A matinée, a Pinter play

Perhaps a piece of Mahler’s

I’ll drink to that

And one for Mahler

Women at the Palm Court, Plaza Hotel, 1970s Getty©

One of Sondheim’s masterpieces, “The Ladies Who Lunch” is a funny, bitter mockery of the well-heeled women who congregate in swanky Upper East Side boites of New York for their lunchtime ritual of chilled fruit cup, Chablis, and chitchat. I’d see these ladies in their milieu at Madame Romaine de Lyon or the Palm Court when my glamorous grandmother treated me to a fancy lunch. They clustered four or five together in the center tables because they were regulars. Perfume and cigarettes swirled around them as they exclaimed over the latest exhibit at the Whitney or the new hairdresser at Alexandre. I think now that some of them must have worn Dior-Dior. It embodied them. Its citrus-aldehyde top notes echoed the frozen charm of their smiles, its elegance matched their crepe de chine blouses. Its animal jasmine and fleshy narcissus smelled of sexual longing, its lilac of loneliness.

Dior-Dior bottle, photo by Lauryn©

Christian Dior-Dior was one of an old guard, a beautifully composed, aldehydic floral, but, with her hints of sex and longing, she was actually ahead of her time. Like those “dinosaurs surviving the crunch” as Joanne describes her crowd, the ladies who lunch are survivors, and, while she may be long out of production, so is Dior-Dior. I find her irresistible.

So, here’s to the ladies who lunch. Everybody rise.

Lauryn Beer, Senior Editor

Editor’s Note: Special thanks to Editor Ermano Picco for his assistance with the history of Dior-Dior