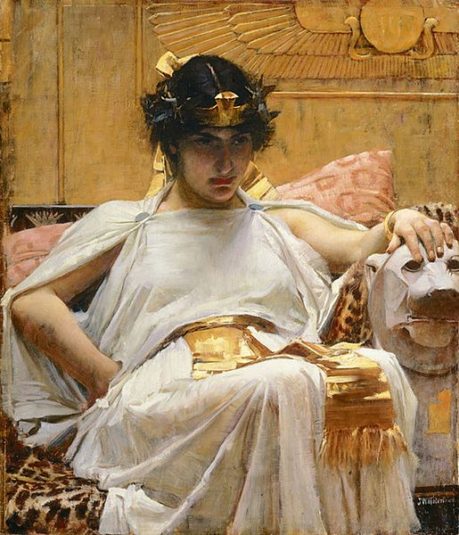

Cleopatra by John William Waterhouse, 1888

The barge she sat in, like a burnish’d throne,

Burned on the water: the poop was beaten gold;

Purple the sails, and so perfumed that

The winds were lovesick with them …

From the barge

A strange invisible perfume hits the sense

Of the adjacent wharfs. –Antony and Cleopatra Act II, scene 2

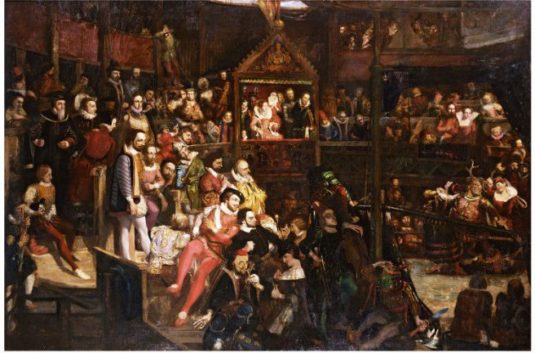

Queen Elizabeth Viewing the Performance of 'The Merry Wives of Windsor' at the Globe Theatre by David Scott, 1840

Fragrance is an unseen but powerful character throughout Shakespeare, and for good reason. The Elizabethan and early Jacobean theatres were redolent with pungent smells. The various odors of humanity would have mingled with the special effects of the day: saltpeter and gunpowder that provided blasts of war, the reek of animal blood used for gore. With such olfactory distractions, how could Shakespeare have realized the tender loves scenes between Romeo and Juliet or summon A Midsummer Night’s Dream's magical forest? Employing the suggestive power of words to activate sense memories in his audience, Shakespeare wove fragrance into his text.

While only the rich could afford perfume proper, Elizabethans commonly used distillations of flowers and herbs in everyday functions and warded off evil smells with spice-filled pomanders that they wore like jewelry and nosegays they carried. They would have readily recognized the numerous flowers, spices and aromas scattered providing immediate sense references. Fragrance in Shakespeare is used to help set scenes, such as the flowery brook where Ophelia drowned, but also to delineate character. But nowhere is the power of fragrance more keenly expressed than in its relations to two of his most enduring female characters; one, whose use of perfume embodies her glamour and showmanship; the other, whose inability to smell anything but blood signals her descent into madness: Cleopatra and Lady Macbeth.

Janet Suzman as Cleopatra, 1974

According to Plutarch, the historical Cleopatra scented the sails of her barge with fragrance. Egypt was the major source of perfume in Cleopatra’s time, and Egyptian perfumes were renowned for their variety and luxuriousness. Oil or wine bases were mingled with combinations of lilies, roses, henna, woods, resins such as oud and benzoin, spices including cardamom and cassia, and khyphi, an incense made with myrrh, honey, raisins, mastic, cinnamon and juniper. Shakespeare’s mercurial queen is a woman of “infinite variety,” suggesting someone with a wardrobe of fragrances at her disposal. The perfume that scented her barge would have differed from the one she wore: one was to impress; the other to seduce. Her sails, needing aromas with great projection to waft over the Nile, could have billowed sweet spice and incense, like DSH Perfumes’ historically-inspired Cardamom and Kyphi (2010). But the hair and breasts of Cleopatra wafted another scent, thick with sensuality, roses, resins and honey mingling with the smell of sex: the unique animalic beauty of a fragrance like Absolue Pour le Soir by Francis Kurkdjian (2010). With its unctuous, syrup roses, sweat of cumin, rich with benzoin and narotic ylang-ylang, this is a perfume to bring an Antony to his knees.

Lady Macbeth, Fall Series, Crow Clipart

In contrast, Lady Macbeth's perfume is marked by its absence. Harrowed by the guilt of murder, Lady Macbeth knows “all the perfumes of Arabia” cannot drown the smell of blood she imagines clings to her hands, washing them over and over in her sleep.

Photo by Steffen Egly, Getty Images

Macbeth opens with witches and descriptions of fog, the forest and blood. It is not hard to imagine the way smoke, most likely from gunpowder, would have hung in the air in the new, enclosed Blackfriars theatre where Macbeth had its premiere in 1606, and how its odor would have lingered throughout the performance. Open a bottle of Leo Crabtree's Beaufort London's splendid 1805 (2015), with its assertive notes of smoke, fir tree, gunpowder and the metallic tang of blood, and the olfactory setting for the Scottish tragedy comes to life.

The Perfume Makers by Rodolphe Ernst, 1854-1932

But the Arabian perfumes Lady Macbeth despairs of? At the time Macbeth was written, Arabia had by succeeded Egypt as the epicenter of perfumery and was known particularly for its rose fragrances. As queen, Lady Macbeth’s perfume would have conveyed status, and might well have been rose mixed with musk – a favourite of Elizabeth I. In Arabian fashion, this perfume might have been spiced with frangipani, a mélange of Middle Eastern spices frequently imported into England. Combine these notes with the wisps of smoke from the candle Lady Macbeth holds in her tainted hand as she sleepwalks, and the perfume she wishes would drown the smell of blood is a sooty rose with dark spice notes like The Different Company’s Rose Poivree by Jean Claude Ellena (2000).

Elizabeth I with a pomander, unknown artist, 1575

It is said that Elizabeth I had a keen nose and required her surroundings to be perfumed. But for the more ordinary folk in his theater, Shakespeare ensured that his verse invoked fragrances to scent the mind.

Lauryn Beer, Senior Editor