Jean-Michel Duriez (Romeo Balancourt Paris Photography)

I had to go to Boston to attend a meeting and because there are no direct flights from Vancouver to Boston, I had to stop someplace on the way. I chose New York because there is a show at the Museum of Arts and Design celebrating the development of fragrance art called “The Art of Scent 1889–2012”. Upon arriving in New York I make my way by subway to the Museum of Arts and Design on Columbus Circle. As luck would have it, Chandler Burr—curator of the exhibit was taking a group on a tour of the gallery. He stopped to give a little spiel about each fragrance in the exhibit, very often comparing it to a period in the history of fine art.

After the exhibit, it was time for the lecture, which featured Chandler Burr, again, and Jean-Michel Duriez, house perfumer for Rochas. It was a participatory lecture in which our participation involved smelling. Before the talk, some assistants at the front were preparing ten bottles of smells and hundreds of thin strips of blotter paper. I'm wondering how they will get all the smells out to the whole audience, in a timely fashion, as Duriez speaks. The first slide says: "One Creation One Material, Lecture at MAD NYC 13 Feb 2013." Wow: 13/02/2013; some kind of palindrome synchronicity pattern thing going on here.

Chandler Burr and Jean-Michel-Duriez

The talk begins and Duriez explains how when one fragrance is created each material has an effect and "how you play with it". Usually, a perfume has a beginning, a middle and an end–like a good story or a good movie. Perfume is time-based like music. You smell one thing at the beginning, then different smells come out in the dry-down as molecules evaporate at different speeds. The pyramid of ingredients; Top, Middle, and Base notes are a function of the volatility of the molecules. Some come quickly like citrus, your first impression of the fragrance, then comes the next ones with lower volatility and finally, after hours, you are left with the bass notes. Base and bass, the same thing; low notes within a composition. But what else is it about these "notes", these molecules, which give them their characteristic smell?

Volatility is just one aspect. There are other factors such as diffusivity. To a perfumer like Duriez, these raw materials are his actors. "We have thousands in our labs and we play with them. We have our favorite actors, and we have some that we never hire. e.g. actors that we cannot manipulate. We have maybe 4,000 or 5,000 actors," according to Duriez. When asked for examples of actors he uses all the time, Duriez says, "Osmanthus. I like it because it is multifaceted, like a good actor, and it has lots of contrasts. Fruit, floral, animalic, leathery." And depending on other ingredients, other supporting actors (molecules) they bring out different facets of osmanthus.

Often you don't smell the supporting actors, but they support the main smell. They really help to emphasize one facet. Movie "extras" are also very important according to Duriez. A fragrance has to have more than two or five ingredients. Sure you can have a string quartet, that is: a perfume with just four ingredients, but typically it requires a philharmonic orchestra, to give the richness of a fragrant work of art. "The streets can't be empty in a movie scene. Extras give richness," says Duriez, pointing out that natural ingredients, such as rose oil contain many molecules; anywhere from 300 – 500 odorous components.

The Dream by Henri Matisse (1940)

Duriez says it takes him a long time to create one fine fragrance. "Let's make a parallel with an art painting. It's a long process. You cannot make a work of art in one attempt. Sometimes it happens, but generally it is a long process of balance. A very long process. Take Matisse's The Dream (1940), at the Met. He did not make this painting right away," says Duriez, as he shows a series of Matisse's sketches he did in the planning of the final painting. "It's not a construction where he added this and this and this. Not a wedding cake. With every mod Matisse makes, the story is slightly changing. I can recreate the fragrance formula at every mod. It's not a decoupage. I like to rewrite at every mod a new story. I think it took Matisse one or two years [in fact it was 9 months] to create The Dream. For me it takes one to two years to make a full perfume. “

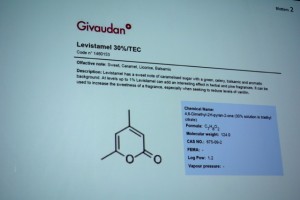

Now we finally get our first smell strip: Yohji Homme, a fine fragrance based on a classic fougere accord containing licorice, leather, rum and coffee. We are also given a second strip with the lead actor in Yohji Homme. It is called Levistamel, invented by chemists at Givaudan, a multi-faceted molecule necessary to create Yohji Homme. Duriez explains the sometimes frustrating process for developing a scent for a corporation: "We had to reduce all the rum, coffee, leather and licorice and we ended up with something quite boring and stupid. In the end I gave them the first sample I created one year before and they ended up saying, 'Jean-Michel, this is what we wanted.' Sigh.”

The next strip is a favorite accord of Duriez's, based on a flower used widely in perfumery, the rose. "It is one I love, but my version. The leading actors are pear ethyl acetate, geranyl acetate, and other secret ingredients." A smell cannot be patented, just as you cannot patent or copyright a recipe for chocolate cake. The only way to maintain your advantage is through secrecy, so perfumers never tell you exactly what is in their creations. Duriez has created a modern rose accord that he may use in other perfumes. Every musician has their signature sound, and so do perfumers.

Photo: Elise Pearlstine

The next smell strip that comes around is not as pretty as a rose. Instead it has an earthy, strong, somewhat harsh inaccessible feeling. The audience is asked for their reaction and we hear, “ashtray”, “burnt rubber”,” fresh and strong”, “nature”, and “coming in from the cold”. It turns out to be the essential oil of ambrette, a member of the hibiscus family, Malvaceae, which is native to India. It's very strong, but it supports the pear and rose. "Ambrette is a link, very chic. Without the ambrette, the perfume is a bit thin," says Duriez. Surprisingly it only represents 0.1 % of the total fragrance molecules in the mix.

Next we are presented a new perfume on strips, a young fragrance, but rich and refined. "I wanted to make a modern Opium, I added more and more fruit, and I ended up with something completely different," says Duriez. This is the perfume ENjoy, by Jean Patou.

Next we encounter a strip containing the vapor distillation of a rose; Rosa Damascena from Turkey, the main actor in ENjoy. Duriez says it’s important to smell the perfume BEFORE you smell the main actor, otherwise your nose will auto adapt to the powerful main actor scent, so that you cannot really smell it, and then when you smell the whole final creation, you won't be able to pick up the main actor in the mix.

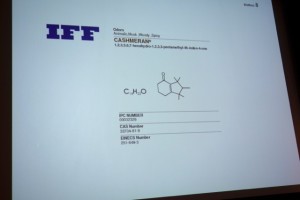

The fourth perfume we smell is Bath and Body Works Moonlight Path. "To support the freshness of tuberose, the leading actor, I used a lot of hedione," says Duriez referring to a jasmine-like synthetic molecule invented in 1962. Then he sent out a smell strip that had us all guessing. Chandler Burr said it reminded him of horses, but a woman in the audience correctly guessed it to be Cashmeran, a synthetic musk and a major supporting actor in Moonlight Path.

The final fragrance was Les Cascades De Rochas : Éclats D'agrumes. The top note is green mandarin from Sicily, along with bergamot and orange. The key supporting actor is Szechuan pepper, though it is not in the pepper family, but rather surprisingly, also a member of the citrus family. Duriez tells us that it comprises less than 0.1% of the formula; otherwise it would have a metallic effect that would ruin the citrus. The pepper oil is a CO2 extract, a technique whereby very high pressure CO2 is passed through a natural material. At that pressure, the CO2 becomes a liquid, and acts as an excellent solvent. When it comes back to normal atmospheric pressure the CO2 simply vanishes, leaving nothing behind but the pure essential oil.

Duriez confessed he is neither a scientist nor a chemist and has little idea of the science behind his scents. He is like a painter unconcerned with the chemistry of cobalt blue or titanium white. While Duriez is not involved with the science behind his art; I am. After the talk I considered the ketones of Levistamel, Cashmeran, and Hedione, and wondered why it is always these functionalities that give a molecule its smell? Is it the series of conjugated double bonds that vibrate like in a dye for coloring? Or is it the shape of an oxygen atom double bonded to carbon? Or is it something else? Until we know, we will never get any wonderful technologies for the nose, as we have for the eyes and ears. As I drifted off to sleep, I wondered if I'd live long enough to get a pair of corrective "smell glasses".

–Barry Shell, Special Contributor