book cover of Les Voluptueuses Une Histoire Parfumée des Femmes de Légende

Élisabeth de Feydeau is a highly-regarded perfume historian and author who has created several important exhibitions (Parfums de Promenade in the Galeries Lafayette, 2001; La Cour des Senteurs de Versailles in 2013,), and participated in many workshops and conferences worldwide. We met 13 years ago at the Hotel Diana in Milan while having cocktails at a party given by former creative director of Robert Piguet Parfums Joe Garces. I was surprised that she knew who I was, because I certainly was familiar with her fascinating books (Jean-Louis Fargeon, Parfumeur de Marie-Antoinette 2005; Les Parfums: Histoire, Anthologie, Dictionnaire, 2011). Frankly, I was in awe of the depth and breadth of her knowledge; as it turned out, she was personable, charming and very modest. In short, delightful.

Élisabeth de Feydeau Wikipedia

In April of this year, I saw that Élisabeth de Feydeau had just published a new history about legendary women and their passion for fragrance: Les Voluptueuses: Une Histoire Parfumée des Femmes de Légende (The Voluptuous Ones: A Perfumed History of Legendary Women). It had just come out on Amazon in French, with no English translation as yet. I ordered it anyway; it’s good discipline to flex one’s somewhat rusty linguistic abilities – and the subject matter provided sufficient temptation. It occurred to me then that you, our readers, might appreciate a book review (until such time as a translated version becomes available).

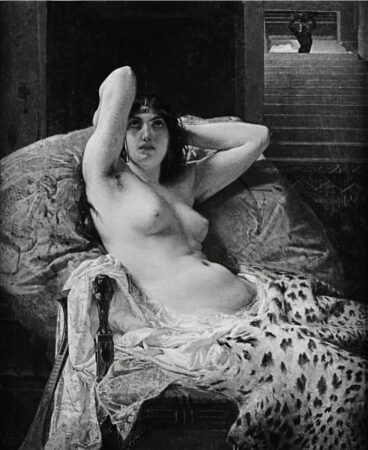

Cleopatra from Les Voluptueuses, Une Histoire Parfumée des Femmes de Légende, by Mosé Bianchi, 1865

A great deal of research has gone into the creation of Les Voluptueuses, including some very ancient tractates: Mme. Feydeau commences with Cleopatra and concludes with Marilyn Monroe. We are familiar with several scented proclivities of these celebrated individuals, but many of the personal details and descriptions of the ways in which they manifested their fervor are heady and perhaps a little shocking for some readers. In Les Voluptueuses, the scholarly marries fun with more than a soupçon of mischief.

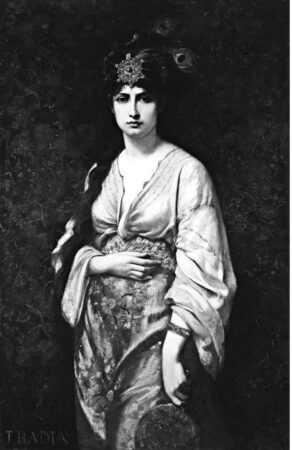

The Queen of Sheba by Jean Jules Badin from Les Voluptueuses, Une Histoire Parfumée des Femmes de Légende

We have read about the mythical myrrh and kyphi of Queen Cleopatra; with the Queen of Sheba, there is less specific documentation, although ancient historians Pliny and Herodotus refer to Boswellia sacra- incense – and styrax. The famous French novelist Gustave Flaubert (author of Madame Bovary) makes mention of labdanum, cinnamon, and agarwood as he describes Makeda/Bilqis, King Solomon’s renowned queen. This is but the tip of the aromatic iceberg.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of perfuming the self, historically speaking – was concerned with hygiene and what was considered appropriate regarding one’s social status. This aspect can’t be overemphasized: women were severely judged by their sillage, the precise nature of it, or the lack of it. Generally speaking, society was obsessed with a woman’s purity – and fragrance played a significant part in how someone was perceived from the very first encounter. Mme. Feydeau examines this over several centuries, through the lens of the lives of famous and infamous women.

“Zitto! mi pare sentir odor di femmina ((Shut up! I I think I smell the scent of a woman.)” ~ Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, Act 1: Shortly after seducing Donna Anna and killing the Commendatore, Don Giovanni has already set his sights upon the hot-blooded Donna Elvira.

Virtuous women were expected to be very subtly scented – or not at all, and this is particularly interesting when one considers a prevailing preoccupation with the ‘odor di femmina’ – the scent of a woman. The reference here is distinctly sexual: it acknowledges the attraction to intimate odor and the need to accentuate it without deliberately calling attention to it. An impossible feat! One was expected to possess a very faint odor which pointed to good hygiene and virginity, and the employment of potent essences such as tuberose and patchouli indicated that one had loose morals. Prostitutes, some mistresses, and demimondaines were easily distinguished by their lavish application of these heady absolutes; no decent woman would be caught applying them to any part of their person – even an innocent handkerchief. Les Voluptueuses goes into great detail when exploring this phenomenon.

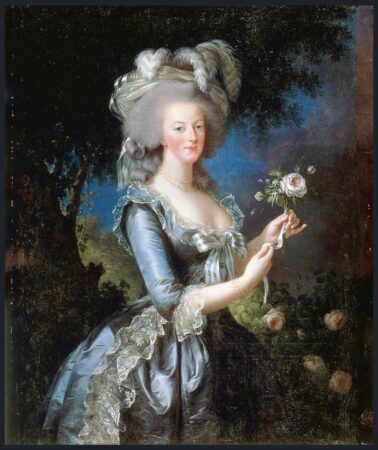

Marie-Antoinette, 1783 (Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun public domain

Unsurprisingly, there were different standards for men and women. Louis XIV was said to have only bathed three times in his life – and he suffered from a fistula between his nose and mouth, which resulted in revolting breath; his wife Maria Theresa had poor, malodorous dentition as well. Both Marie-Antoinette and the Marquise de Montespan employed the skills of a court perfumer in order to mask the unpleasantness of king and courtiers alike, and attended carefully to their own personal toilette. Le Roi changed his shirts frequently in an attempt to control strong body odor – and only spot-washed portions of his royal person prior to intimacy – but he did rub himself down regularly with alcohol and perfumes.

Marquise de Montespan (public domain)

This accounts for the widespread use of scented pomades, perfumed and powdered wigs, handkerchiefs drenched in eau de cologne, perfumed pastilles for the breath, and scented sponges. Bathing was thought to ‘open the pores’ and render the populace more vulnerable to communicable diseases. It is small wonder the the court of Versailles was notoriously foul smelling.

Empress Josephine (Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, 1805)

“Ne te lave pas… J’arrive!” (don’t wash … I’m coming), is attributed both to King Henry IV (who is said to have written it to his mistress Gabrielle d’ Estrées) and Napoleon Bonaparte (in a missive to Empress Josephine).

1856 John Simpson Queen Victoria

Who can forget two wildly differing sensualists – Empress Josephine, who reeked of musk; of whose natural odor Napoleon was besotted? Or the less revealed young Queen Victoria, who was smitten with orange blossom and myrtle all her life? We have come to remember the queen in mourning, ignoring her passionate love of fragrance, food, and dancing – as well as the aroma of handsome young men. Mme. Feydeau sheds new light on these two – along with so many other illustrious women.

Colette in Rêve d’Egypte via Wikimedia Commons

Two of the most unabashedly fragrant women were the actress (and talented sculptor, playwright, and memoirist) Sarah Bernhardt and Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette. Each lived what was considered a scandalous life, during which their sexual preferences were fluid and impassioned. Both individualists, they pushed the boundaries of art on many levels – and were hedonistic in the extreme. Both women adored makeup and perfume, and were affiliated with beauty products bearing their name. Colette even created many of her own specialties and sold perfume (her lifelong signature was Jasmin de Corse by Coty) – while Mme. Bernhardt surrounded herself with exotic flowers, entranced by ylang-ylang, which the Maison Rigaud popularized.

Sarah Bernhardt Via Wikipedia

She adored perfumes from the East all her life, and was very close to Pierre-François-Pascal Guerlain, to whom she referred as ‘the prince of perfumes’. It is said that Jacques Guerlain created a particular fragrance for her alone, inspired by Art Nouveau – but its aroma and name have been lost to the annals of history.

I don’t envy Mme. Feydeau the Herculean task of assembling the sagas of so many fascinating personae. I couldn’t include them all, of course. Amongst them are women who altered the course of history as wives, mistresses, artists, and those who wielded significant political influence. Les Voluptueuses is a most compelling read and obliges one to view our culture through a more evolved olfactory lens.

Une Histoire Parfumée des Femmes de Légende was purchased and translated by me.

~ Ida Meister, Deputy and Natural Perfumery Editor

Michelyn’s Note: Élisabeth de Feydeau was a Guest Contributor for us in 2013 Mystery and Muses: CHANEL N°5 CULTURE Exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo

Follow us on Instagram @cafleurebonofficial @idameister @elisabethdefeydeau @flammarionlivres

Available on Amazon.com Flammmarion

This is our Privacy Policy