Visualizing the Invisible

Visual Metaphors of the Scented World

In the work of John Singer Sargent, Pierre Bonnard,

and Michel Roudnitska

Woody Oriental/Oriental Boise

(http//www.fragrancesoftheworld.com)

Imagine that you are taking a course in painting. After having done landscape and still life paintings, your instructor asks that you render the scent of your favorite perfume. Where would you begin? What images come to mind? What lines, forms, and colors would you apply to the canvas? If you find yourself drawing a blank, do not be discouraged. The complexities are immense.

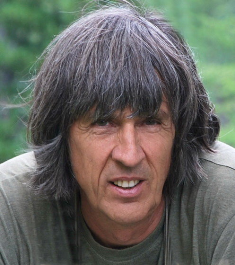

When I asked Michel Roudnitska, world-renowned perfumer and visual artist, to address his process of creating a visual metaphor, he responded :

"Transforming a scent into a visual representation is the result of 20 years of research about the correspondences between olfactory shapes and visual structures, through the emotions related to these forms and colors. It's an intuitive process which led me to elaborate a kind of graphic vocabulary with simple elements to express the main olfactory descriptors as: fresh, green, powdery, tart, floral, woody…The next step was to combine these elements into compositions in order to represent complex fragrances".

As Roudnitska emphasizes, it takes many years of study to delineate the affinities between olfactory and visual forms, and a key factor in this transcription lies in the emotions that share aspects of both. Roudnitska’s artwork depicting the various fragrance families and their related scents appears in the book, Fragrances of the World 2010 (http//www.fragrancesoftheworld.com). It is a brilliant testimony to the outcome of his research. In addition to his contemporary representations, the paintings of two artists from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries provide examples of superb visual metaphors: John Singer Sargent’s Smoke of Ambergris (Fumee d’amber gris), 1880, and Pierre Bonnard’s The Bathroom (Le Cabinet de Toilette), 1908. A closer look at the work of all three artists reveals the fascinating intricacies and equivalences involved in transcribing the world of scent into the domain of the pictorial.

John Singer Sargent

Smoke of Ambergris, 1880

Smoke of Ambergris by Sargent is a visual metaphor for the sacred power of scent as it crosses boundaries and penetrates both the inner life and garments of a meditating woman. Spiritual purity is conveyed by the lush and profuse use of white paint in both the woman’s garments and the walls and pillar that surround her. Radiant shades of white dominate the painting as broad strokes of paint sweep the eye upward in holy ascent. The standing woman captures the scent of ambergris by forming her cape into a canopy held over her head. Her facial expression appears calmly focused and meditative; her posture is one of dignity and patience as the smoke bathes her clothes and breath. The fact that the incense rises and the woman stands erect embracing it, underscores both her receptivity to the divine ascending within her and the penetration of the sacred smoke as an incarnation of that divine ascension. She herself is painted in a mixture of gray and white shades that soften and flow into one another. These shadings, occupying most of the space in the painting, create an expansive luminosity that is a metaphor for the sacred force of the incense and also for the experience of the transcendent that it embodies. It highlights the vapors being absorbed into the woman’s clothing and inner self, as the rising spire of smoke merges with the gray shading of her gown. Nothing that concerns the worshiper is sharp or angular. Her features are delicate and the lines in her clothing are curved. Her garments drape and fall in folds. She herself rises like a soft shrine behind the smoking ambergris, emphasizing the gentle quality of its redolence.

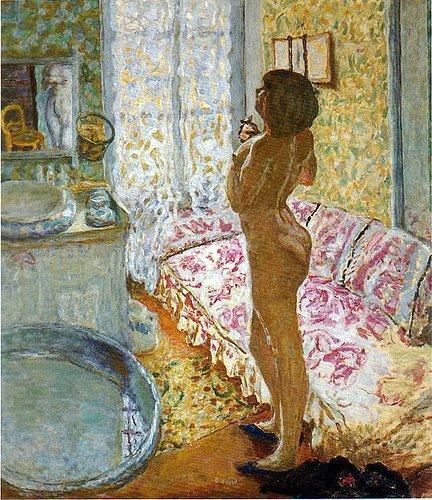

Pierre Bonnard

The Bathroom, 1908

Whereas Smoke of Ambergris is done in luminous white and gray tones, Bonnard’s The Bathroom is on fire. The visual representation of scent becomes a conflagration of color and light in this exquisite painting. We move from the sacred to the erotic, albeit one not lacking in a certain divine element. Light streams through the painting, setting aflame the curtains and their golden appliqués as well as the yellow painted into the wallpaper and rug. The feeling of heat is created by both the red in the sofa and the gold in the curtains. One feels the trembling of light and heat in the wavelike lines Bonnard uses in his painting of the appliqués as well as the designs in the slipcover and rug.

The light is predominantly golden and finds its radiant match in the bottle of perfume held by Marthe, the woman in the painting who was also Bonnard’s wife. Indeed, the bottle seems to be at the center of all this luminosity along with the scented body of the woman. Both appear to generate the heat and radiance shimmering in the room. One reason for this is that both share in the yellow and golden tones so predominant throughout this painting. If one looks closely at the woman’s flesh tones, one can see the same yellows that are in the room. Sunlight limns her body. It is created by using lighter tones down her back, arms, breast, and buttocks.

In this work light is a visual metaphor for fragrance. Just as light fills space with its heat and brilliant rays, perfume fills the air with its scented vapors and effusive molecules. Bonnard has visualized the invisible; given perfume a discernible presence; but he has also done more. He has symbolized how the woman is cleansed and reborn through the ritual of the bath and perfume. By cleansing herself, the woman undergoes an emotional as well as physical transformation. She steps out of the dull, pragmatic concerns of the everyday, symbolized by the grays in which the dresser and tub are painted, and enters into the spiritual world that perfume creates. Here is how Stamelman describes it:

Perfume speaks the body; it is the body but in a different form. It enables the body to change its presence in the world, modify its signature and redefine its identity".

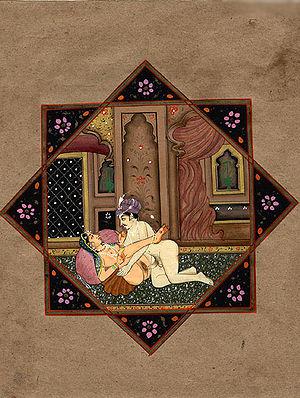

To choose a perfume is to assert one’s body, or more precisely to choose a certain way of being that body. As early even as the sixth century, a woman’s beauty, according to the Kama Sutra, was determined not by her physical appearance but by her odor (p. 18).

Bonnard has painted Marthe in a firm stance, feet solidly planted on the floor, back beautifully arched, chest held forth to the light. She absorbs and generates light but unlike the light, is full-bodied, fleshy, sensual. Here is an exquisite symbol of the spirituality of perfume as a mysticism of the senses. Scent vaporizes the body and bears it aloft at the same time that the body is the origin and home of its aromatic effusions.

In contrast to the work of Sargent and Bonnard, the images of Michel Roudnitska draw the viewer into a sensual, emotional, and visionary realm of specific fragrance compositions. In Fragrances of the World he gives artistic expression to the various fragrance families articulated by Michael Edwards; over a dozen stunning images result. The Oriental family, considered here, is described in the book as follows: “Orientals are the exotic queens of perfumery. [They are] Sensual, often heavy, blends of oriental resins, opulent flowers, sweet vanilla and musks….the appeal of the full-bodied, take-no-prisoners Orientals endures (p. 54).”

Oriental -Michel Roudnitska (from Fragrances of the World, 2010

Roudnitska’s image has a vibrancy and vitality that pulls the viewer immediately into the ecstatic desire, passion, and heat embodied in an oriental perfume. His large, sensuous rose bursts into a spire of flames. Bright saturated reds and light yellows glow so intensely against a radiant black background, that their colors vibrate beyond the page and into the viewer’s vision. The spire, done in bright tones of red and light yellow, rises like an undulating column to the topmost border of the work. Flames that are even more translucent and delicate emerge from it, flare upward, and then dissolve into the black background. Here is a representation of scent as it streams from the red rose, at first strong in impact and then becoming more and more diffuse until it evaporates completely. The heavy luxuriance of its aroma is given in the densely packed profusion of petals, the joyful excess of red, and the clustering of the most finely detailed images throughout the lower half of the work. The emotional qualities symbolized by these elements are ecstatic, burning, passionate, inflammatory, and impulsive. The scent itself is shown to have warm, narcotic, even hallucinatory qualities. Staring at the images, one becomes hypnotized by the almost blinding effulgence of color that Roudnitska incorporates. The red of the rose is done in counterpoint with deep recesses, formed by its profusion of layered petals. Here the color shades slowly into a radiant black, so that a relationship forms between the all black background and the rose with its flame. The effect is that the rose appears to be one with its background, the work achieving a structural unity of its various elements.

All of the lines, contours, and forms of the rose have soft, curved, and flowing dimensions. Even its saturated red conveys softness. This plush undulation of elements, together with the rose’s fiery emanation, result is an expression of luxurious eroticism, evoking both the flesh of the human body and a seductively enveloping fragrance. Roudnitska surrounds this eroticism in mystery, symbolized by the black shadings in the rose and its background.

In addition to this erotic mystery, Roudnitska’s visual image evokes a mystical quality. He succeeds, as did Bonnard, is rendering a mysticism of the senses. The flesh of the rose gives birth to the ethereal flame of scent; in essence, the rose volatilizes itself, sending its invisible fragrance into the ambient atmosphere; however, the source of that scent remains the lush, visible body of the rose. Diffuse, mystical sensibility is incarnate.

Photo: 1er Mai Day Diorrisimo's Day (Courtesy of Michel Roudnistska)

Sargent, Bonnard, and Roudnitska each create visual metaphors of scent using diverse artistic techniques that add up to more than the sum of their parts; they become unique and stunning visual representations of the scented world. Each world is a complex expression of the emotion, atmosphere, relationships, and settings that visualize their invisible subject, fragrance. Through their work we come to understand visually the profound meanings that the art of perfumery articulates. Eros, spiritual longings, life, death, mystical and sensual transformations, are all communicated in its olfactory effusions. In understanding and expressing this phenomenon so lucidly, these three artists have made an inestimable contribution to both the visual and scented arts.

Marlene Goldsmith, Contributing Editor

Editor's Note: Many thanks to Michel Roudnitska for granting permission to use his images from the book, Fragrances of the World, and for taking the time to respond to Marlene's questions regarding the creative process.

Edwards, Michael and Roudnitska, Michel. Fragrances of the World 2010.

http//www.fragrancesoftheworld.com.

History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present. New York: Rizzoli, 2006.