2006 was the year that I knew I would soon leave my career as a corporate marketing executive and that a fragrant path awaited me. It was also the year I discovered Paestum Rose Eau de Toilette by Eau D’Italie, one of the first perfumes that I identified instinctively as contemporary olfactive art.

Paestum Rose challenged the idea that rose fragrances should smell fresh and dewy, like a bloom plucked from a garden. I would wear Paestum Rose and envisage the paintings of Caravaggio. This was a rose that defied conventional idealization of pretty and had a heart of shimmering darkness and dusky colors seen in the paintings of the Old Masters. I inhaled ancient aromas of dark wood, dusty incense and wild roses pushing through ancient wet stones; yet Paestum Rose seemed startlingly new. Two years later I met Bertrand Duchaufour, “the painter” for the first time. It was also the year I met Sebastián Alvarez Murena, the “patron” and one half of the husband and wife team behind Eau D’Italie over an enlightening lunch at Fred’s at Barney’s New York (during the launch of Baume du Doge). There is a piece of both Sebastián and Marina and their love for the rich culture and history of Italy in each fragrance; it was at this meeting I understood the importance of creative direction in perfumery.-Michelyn Camen, Editor-In Chief

Sebastián Alvarez Murena and Marina Sersale

I think that what defines most Marina and I as creative directors is, ironically, the fact that we don’t want to be in the limelight. This, in part because it is our nature, but also because in our opinion pride of place in what we do should be taken by one thing only: the fragrance itself.

This kind of approach has been for centuries the backbone of craftmanship in Italy, a country where for every great artist there were hundreds of marvellously talented craftsmen that made it all actually possible. Not only did they create all sorts of beautiful things, they also made up an extraordinary creative humus the result of which is still visible today. That is why the key word for us is “craft”, as in the spirit of an artisan, who will always put his product ahead of himself, since that is the one thing he is most proud of.

Let’s admit however, that there is often a component of voyeurism in each one of us, which makes us want to know more about the “behind the scenes” of everything, be it – as in our case- the creation of a fragrance, or in the case of a writer, composer or designer, anything or anyone that intersects with their private life in one way or another.

This natural inclination has been cleverly compounded by modern marketing, and today we find ourselves knowing more about things than was ever the case in previous times. In the past, fragrance marketing was more reliant on the idea of rarity, based on that principle commented by Jean-Paul Sartre by which the rich (and who if not the rich, or the aspiring classes, were the par excellence customers of fragrance in the past?) delight in knowing the cost in human work and effort of whatever they use, have, wear: the fabric made by young girls in Kashmir or the extract which can be found only in the distant country of x y and is brought on camel back through a desert, and so on.

Instead modern times have brought not only a more democratic approach to the use of fragrance, but also a higher appreciation of the skills needed to create a fragrance, instead of mere reliance on raw materials.

Enter the craftsmen: in fragrance this is the person who knows how to blend raw materials so that two elements combined smell like a third one, and who manages to evoque a conceptual smell and to conjure it up in a bottle. And also the person who gives the idea… Sometimes, more often than people realise, the person who has the idea is the perfumer itself. Other times it’s someone else, i.e. a creative director. But it’s always up to the perfumer’s talent to manage to translate an idea into actual fragrance.

Marina and I came from different fields. Marina was a documentary film maker, whereas I was a journalist. We had no formal training in perfumery, if you except a training in aromas I’d had as a young man. And yet, when the moment came of creating what was then to become Eau D’Italie, we had no doubts on what we were looking for.

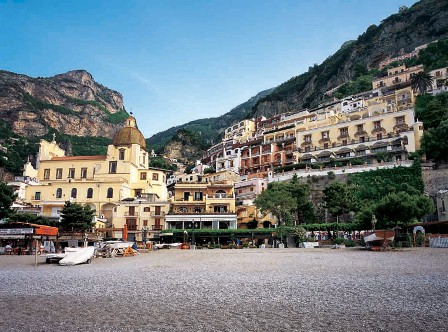

But let me take one step back: in 2001 Le Sirenuse, the hotel founded by Marina’s father and his siblings in Positano, on the Amalfi Coast, was about to turn 50. A huge party had been organised for October that year, a party for friends all over the world. And then 9/11 arrived, and of course no one felt like partying anymore. The only proper thing to do was to cancel it, and so it was done.

It was a few months later, in February or March 2002 that, while sitting on the terrace of the hotel, the idea came up that there had been an anniversary, and that it hadn’t been properly celebrated. To make a long story short, the idea of a fragrance came up and Marina and I took up the project, giving ourselves a series of strict rules, first of which that we had to make something totally new.

The fragrance we wanted to create was to be an Italian Eau de Toilette of the 21st century, something to be thought of in the future as a benchmark of Italian perfumery. So no fake old formulas found in drawers or traditional recipes from a great-grand-mother, it had to be something new, created from scratch. And it had to be something different from the usual citric fragrances that for some reason are thought to be The Italian classic fragrance.

It also had to be an urban fragrance, not something that would be only a memory of Positano, but a fragrance that could have an independent life on its own in Rome, Milan, New York or London. On top of all of this, it had to reflect the spirit of Le Sirenuse and its heritage. And this was no easy task, because Le Sirenuse really defies any labelling: it is both very classic, as in Neapolitan 18th century, and at the same time very contemporary, with some parts of it designed by architect Gae Aulenti (who sadly died recently) and which reflect her clean, elegant and balanced style.

We had decided that the fragrance was to be inspired by what, for us, is the smell of Positano in summer, a mineral smell, of terracotta heated by the sun, the terracotta of tiles on roofs and terraces. Hard to describe in words, yet, if you have been to Positano in summer (or if you smell Eau d’Italie EdT), you will know what that is.

How to put all this in a bottle…?

Enter Bertrand Duchaufour…

Our first encounter with Bertrand was on a professional basis, but I think we very quickly became very fond of each other, and we are now close personal friends. But let’s go back to that time, ten years ago: it was extraordinary with how much precision Bertrand got to what was to be the heart of the fragrance, an accord we called “argile”, as in “clay”, and around which we then “embroidered” the rest of the notes. And I think that precision is the key word to understand the nature of how we work.

I remember that once, during the development of Magnolia Romana, which was not an easy task at all, we had reached a point in which we felt we had lost our way. We knew where we wanted to get, but couldn’t seem to manage. Eventually we got there, but it was by doing a series of very precise little changes, which made a big difference in the end. It was done with what Bertrand described as “millimetric precision”.

Of course the more you work together, the easier it becomes, the more you know each other, the easier it is to work with a perfumer, you develop a language you share. And yet there were some cases in which the process was totally the opposite:

When we started working on what was to become “Au Lac”, we asked not to be told who were the perfumers who were sending submissions for our brief. We wanted to know as little as possible of the person we were working with, because we felt that if we knew who it was we would have been influenced by his or her previous works. Eventually we wrapped up “Au Lac” and only then we asked who was the person we had been working with all along. It was Alberto Morillas…

Is there an influence of the creative directors’ life in our fragrances? Of course there is, I think it couldn’t be otherwise. If we take for good the scientific principle by which by merely observing a phenomenon you alter it, you can imagine to which point a fragrance is steered to reflect ourselves and what we were looking for in that fragrance. Where it only because there was one more rule we gave ourselves before starting, and which we have never given up on. That is the rule that if we are not 100% satisfied, personally satisfied, with one of our products, we will simply not launch it.

This was the “eleventh commandment” we gave ourselves when making our first fragrance, Eau d’Italie Eau de Toilette: if we are not totally, completely happy with it, and can be proud of it, we’ll just not launch it. No one obliges us to do so, and I think this is the one and great difference between niche fragrance houses and commercial fragrance houses: we can decide what to do with much less pressure.

Our management style is very simply described: obsessive. Eau d’Italie is our creature, and each element, each detail, each thing in it has been thought of and is there for a reason. We always think “would I be THRILLED if I bought this?” And unless the answer is “yesss!!!”, we are not happy.

To be frank, I think there’s always a risk in saying things like “art influences our work”, and things like that. I’ve always found slightly tragic the need to assimilate one’s work with higher things like art. And yet…

…the truth is that, even if one tried not to, if you live in Italy there’s no way of not being constantly influenced by art and by beauty. I wasn’t born in Italy so I can say this as someone who arrived here at the age of ten, and still doesn’t stop being surprised day after day: there’s no country in the world that has so much beauty, all together, often all at the same time. How could you possibly not be influenced?

In our case, of course, having chosen to represent Italy, and many things Italian, in our fragrances, we are constantly on the look out not only for smells, but also for shapes, colours, shades. The colours of our fragrance “Sienne l’Hiver“, for instance, are for us the colour of a winter sky in Siena. Which turns out to be kind of sky you could see in the background of a Renaissance painting…

Come to think of it, there’s even one of our fragrances that was actually based on an concept expressed by a famous artist, Umberto Boccioni, one of the founding fathers of Futurism. The fragrance is “Au Lac”, which was our first floral, and which we wanted to be a “special” floral. The gestation of the idea was long, very long, but one day a book we were reading showed us the way.

The book was written by a friend of ours, Marella Caracciolo, and it was a beautiful chronicle of the love story between Umberto Boccioni and Princess Vittoria Colonna, a secret love story in a tiny island on lake Maggiore, in the summer of 1916. At some point Boccioni sees the garden of the house, a gorgeous, classic Italian garden, and obviously is struck by its beauty. But being a Futurist he can’t confess that he likes something classic, so he comes up with this idea of a “Futuristic garden”, and that’s when we started thinking about what subsequently became our beautifully contemporary floral…

You see, I said we didn’t like to speak about ourselves, and about the relation with art, and yet…

Beware of one thing, though: talking of art must never mean that one overlooks innovation.

Innovation, I think, is another key word of the way we work. This, again, is no different from what has been tradition in this country for centuries, the push for innovative, new, better ways of doing beautiful things. I’m afraid that I’ll have to resort again to a comparison to art, but when Leonardo da Vinci was experimenting with new pigments in the Renaissance, he wasn’t doing anything less than innovating. (He didn’t always succeed with pigments, if think of “The last supper” in Milan. But when he succeeded, which was most of the time, brace yourself!) Ditto for, earlier on, Giotto moving ahead of Medieval canons of painting before anybody else. All this, to say that obviously innovation has been a characteristic of the search of beauty in the West, as opposed to the East, where excellence has been found in repeating the same model over and over again along the centuries.

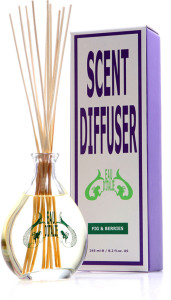

It’s in this spirit (mutatis mutandis, of course!) that we faced the development of our new home scent diffusers: they had to be alcohol-free, and yet had to be super performing, better that anything than is already on the market, and while managing to maintain the delicate fragrant notes. An apparently impossible task, and yet we managed, thanks to a brand-new state of the art solvent formula that works like no other: it works infinitely better, is more performing and has a “linear”, very steady kind of diffusion. It seemed impossible, and yet there they are, for anybody to try. Innovation at work…

–Sebastián Alvarez Murena and Marina Sersale, Founders and Creative Directors of Eau D’Italie

Thanks to Sebastián, Marina and the US distributors Lafco NY we have a reader’s choice draw for:

2004- Eau d’Italie Eau de Toilette by Bertrand Duchaufour

2006- Paestum Rose by Bertrand Duchaufour

2007 Bois d’Ombrie by Bertrand Duchaufour

2007 Sienne L’Hiver by Bertrand Duchaufour

2008 Baume du Doge by Bertrand Duchaufour

2009 Magnolia Romana by Bertrand Duchaufour

2010 Au Lac by Alberto Morillas (Mark’s review here)

2011 Jardin Du Poete by Bertrand Duchaufour (CaFleureBon Best of ScentTop 25 of 2011 and Mark’s review here)

2012 Un Bateau Pour Capri by Jaques Cavallier (Mark’s review here)

To be eligible please leave a comment on what you have learned or what was memorable about Sebastián Alvarez Murena and Marina Sersale as creative directors in perfumery as well as the fragrance you would like to win. Draw closes January 17, 2013.

LIKE CaFleureBon Creative Directors in Perfumery Facebook page. Your comment will count twice.

Editor’s Note: All images are used with permission of Eau D’Italie

We announce the winners only on site and on our Facebook page, so Like Cafleurebon and use our RSS option…or your dream prize will be just spilled perfume